Gerrards Cross

| Gerrards Cross | |

|---|---|

| Town and civil parish | |

Gerrards Cross Town Centre | |

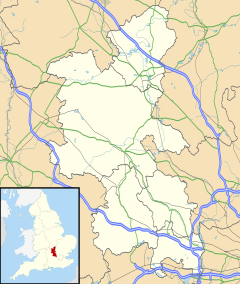

Location within Buckinghamshire | |

| Area | 10.88 km2 (4.20 sq mi) |

| Population | 8,017 (2011 Census)[1] |

| • Density | 737/km2 (1,910/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TQ00258860 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Gerrards Cross |

| Postcode district | SL9 |

| Dialling code | 01753 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

Gerrards Cross is a town and civil parish in south Buckinghamshire, England, separated from the London Borough of Hillingdon at Harefield by Denham, south of Chalfont St Peter and north bordering villages of Fulmer, Hedgerley, Iver Heath and Stoke Poges. It spans foothills of the Chiltern Hills and land on the right bank of the River Misbourne. It is 19 miles (31 km) west-north-west of London. Bulstrode Park Camp was an Iron Age fortified encampment. The town is close to M25 motorway and the M40 motorway runs beside woodland on its southern boundary.

History

[edit]The site of a minor Iron Age hillfort, Bulstrode Park Camp, is to the south-west of the town centre. It is a scheduled ancient monument.[2]

The area which is now Gerrards Cross was historically an area of wasteland known as Chalfont Heath, which later became known as Gerrards Cross Common. In the medieval period, there was no village in the area, which straddled the edges of five different parishes. The name Gerrards Cross, sometimes spelled Jarretts Cross, is recorded from at least 1448, and may relate to an early landowner, Gerard of Chalfont, who is recorded as having owned land in the area in the 14th century.[3]

The origin of the 'cross' element of the name is uncertain; a cross is marked on early maps near the Bull Hotel and Latchmoor Pond at the western end of the common, but whether it was a standing cross marking a boundary or meeting place, or a name for a crossroads is unclear. The modern crossroads of the Oxford Road (the A40) and Windsor Road / Packhorse Lane (B416) was not created until 1707, when an old north-south road through Bulstrode Park was diverted, which was many years after the name Gerrards Cross was first recorded.[3]

Until the 19th century, development in the area was limited to a small number of buildings immediately adjoining the common, most of which were in the parish of Chalfont St Peter.[4]

In 1859, St James' Church was built of Oxford Road.[5] It was initially a chapel of ease for the parish of Fulmer in which it lay, but in 1861 it became parish church of a new ecclesiastical parish called St James, Gerrard's Cross, created from parts of the parishes of Chalfont St Peter, Fulmer, Iver, Langley Marish, and Upton-cum-Chalvey.[6] The creation of the ecclesiastical parish did not change the civil parish boundaries. A new civil parish of Gerrards Cross matching the ecclesiastical parish was subsequently created in 1895.[7]

Gerrards Cross remained a relatively small village at the turn of the 20th century. The parish had a population of 552 at the 1901 census.[8] In 1906, Gerrards Cross railway station opened on the Great Western and Great Central Joint Railway, a new line jointly built by the two companies to improve their routes from the Midlands to London. The station is to the north-east of Gerrards Cross Common, and the area around the station was developed soon after the station opened; by 1911, the population of the parish had grown to 1,612,[8] and it then grew steadily throughout the 20th century.[9]

Facilities

[edit]

The large and distinctive parish church is dedicated to St. James. It was built in 1861 as a memorial to Colonel George Alexander Reid who was MP for Windsor, and designed by Sir William Tite in yellow brick with a Byzantine-style dome, Chinese-looking turrets and an Italianate Campanile. In 1969 the singer Lulu married Maurice Gibb of the Bee Gees in the church. The actress Margaret Rutherford is buried with her husband Stringer Davis in the St James Church graveyard.

The town has its own library and its own cinema, the Everyman Gerrards Cross, which originally opened in 1925.

Independent schools include St Mary's (all girls- through to sixth form). Students of secondary school age attend either one of the local grammar schools, such as Dr Challoner's Grammar School (Boys with co-educational Sixth Form), Dr Challoner's High School (Girls), The Royal Grammar School, High Wycombe (Boys), John Hampden Grammar School (Boys), and Beaconsfield High School (Girls) Chesham Grammar School (Co-ed), and the local Upper School, Chalfonts Community College, which is the catchment school.

On the south side of the town is the Gerrards Cross Memorial Building, on the site of the former vicarage. The building was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and unveiled in 1922 to commemorate the town's losses during the First World War. It is the only example of a Lutyens war memorial designed with a functional purpose.[10]

Governance

[edit]There are two tiers of local government covering Gerrards Cross, at civil parish (town) and unitary authority level: Gerrards Cross Town Council and Buckinghamshire Council. The town council meets at the Gerrards Cross Memorial Centre on East Common and has its offices at the adjoining South Lodge.[11][12]

From the creation of the civil parish of Gerrards Cross in 1895 until 1974 it was included in the Eton Rural District.[13] The parish then became part of the Beaconsfield district in 1974, which was renamed South Bucks in 1980.[14] The district was abolished in 2020, when Buckinghamshire Council was created, also taking the functions of the abolished county council.[15]

Since 1974, parish councils have had the right to declare their parishes to be a town.[16] Gerrards Cross Parish Council declared the parish to be a town with effect from 1 January 2016. The council therefore became Gerrards Cross Town Council.[17]

Transport

[edit]

The town has a railway station on the Chiltern Main Line which opened on 2 April 1906. This provides services to London, High Wycombe and Oxford with a commuting time of 18 minutes on the fast train to London Marylebone. A new arch over the section of deep railway cutting to allow Tesco to build a supermarket collapsed on 30 June 2005 at 19:30. Nobody was injured but the line was closed for over six weeks. Compensation by Tesco to Chiltern was reported as £8.5m and the retailer compensated by funding a media campaign to reinstate business immediately lost by the closure. Construction of a correctly constructed arch began in January 2009.[18]

The 11.36am from London Paddington to Gerrards Cross was an official or 'parliamentary train' recognised as an outlandish loss-making service to prevent the link to that terminus being closed or re-allocated. This train now terminates at West Ruislip. In 2011, National Rail was lobbied to phase the service out.[19]

The town lies 8.4 miles (13.5 km) north west of London's Heathrow Airport.

Demographics

[edit]In the 2021 Census, the largest religious affiliations[20] in Gerrards Cross were Christian (46.2%), those with no religion (22.4%), Sikh (10.5%), Hindu (7.5%), Muslim (6.4%), Jewish (0.8%), Buddhist (0.5%) and Other (0.5%).

It was reported 65.5% of people living in Gerrards Cross were reported as White (65.5%), Asian (25.5%), Mixed (4.0%), Black (4.0%) and Other (1.1%).[21]

Recent history

[edit]Many houses built during development in the 1950s had defective tiles, leading to the highest court reported judgment Young & Marten Ltd v McManus Childs Ltd,[22] holding that a person who contracts to do work and supply materials implicitly warrants that the materials will be fit for purpose, even if the purchaser specifies the materials to be used.

| Output area | Homes owned outright | Owned with a loan | Socially rented | Privately rented | Other | km2 roads | km2 water | km2 domestic gardens | km2 domestic buildings | km2 non-domestic buildings | Usual residents | km2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Civil parish | 1311 | 1014 | 123 | 384 | 58 | 0.787 | 0.079 | 2.728 | 0.353 | 0.070 | 8017 | 10.88 |

Notable people

[edit]- Matt Aitken, song writer, record producer and musician from Stock Aitken Waterman lived in Gerrards Cross.

- Roy Castle, dancer, singer, comedian, actor, television presenter and musician, lived in Gerrards Cross.

- Amal Clooney, barrister and human rights activist, moved from Lebanon to Gerrards Cross with her family at the age of 2.

- Angela Douglas, actress, born in Gerrards Cross 29 October 1940.

- Helen McKay, singer, first person to sing on the BBC Television Service, 26 August 1936, lived in Gerrards Cross.

- Kenneth More, actor, born in Gerrards Cross 20 September 1914.

- Des O'Connor, entertainer (died in November 2020)

- Dominic Raab, politician, Conservative Member of Parliament for Esher and Walton and former Deputy Prime Minister, Secretary of State for Justice, Lord Chancellor and Foreign Secretary, grew up in Gerrards Cross.[23]

- Joan G. Robinson, author and illustrator, lived in Gerrards Cross. Her best-known book is When Marnie Was There, which was adapted into an animated film by Studio Ghibli.

- Peter Stringfellow, businessman and nightclub owner, lived in Gerrards Cross (died 7 June 2018).[24][25]

- Benjamin Zander, composer, born in Gerrards Cross 9 March 1939.

Literary references

[edit]Gerrards Cross was one of the locations for the crime thriller “The Stalkers” (2013) by Paul Finch, a former police officer and journalist and now a full-time writer.

Gerrards Cross also featured in a true story about love and war based on real letters “The Very White of Love” (2018) by S.K. Worrall.

In the story “Carousel” (2013) depicting a spoiled boy from an Indian family the author Rajeev Rana also placed some of the action in Gerrards Cross.

This town also served as the setting for the novella “Amy's Travels” (2024) by Lilly Khripko (born in 2013 in the UK and now living in Gerrards Cross). The book tells the story of a tweenage girl recalling her early childhood.

References

[edit]A History of Chalfont St Peter and Gerrards Cross C G Edmonds 1964 and The History of Bulstrode by A M Baker 2003 published as one book by Colin Smythe Ltd. 2003

- ^ a b Neighbourhood Statistics 2011 Census Archived 22 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 2 February 2013

- ^ Historic England. "Bulstrode Park camp (1006954)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ a b Hunt, Julian; Thorpe, David (2023). Gerrards Cross: A history. Phillimore. ISBN 9781803994024. Retrieved 19 February 2025.

- ^ "Buckinghamshire Sheet XLVIII". National Library of Scotland. Ordnance Survey. 1883. Retrieved 19 February 2025.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of St James (Grade II*) (1124389)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ "No. 22502". The London Gazette. 16 April 1861. p. 1577.

- ^ Langston, Brett. "Eton Registration District". UK BMD. Retrieved 19 February 2025.

- ^ a b Kelly's Directory of Buckinghamshire. 1915. p. 105. Retrieved 19 February 2025.

- ^ "Gerrards Cross Chapelry / Civil Parish Population". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 19 February 2025.

- ^ Historic England. "Gerrards Cross Memorial Building (1430052)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ "Meeting Agendas and Minutes". Gerrards Cross Town Council. Retrieved 19 February 2025.

- ^ "South Lodge and North Lodge, 7 and 9 East Common". Local Heritage List. Buckinghamshire Council. Retrieved 19 February 2025.

- ^ "Gerrards Cross Chapelry / Civil Parish". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 19 February 2025.

- ^ "No. 48075". The London Gazette. 23 January 1980. p. 1130.

- ^ "The Buckinghamshire (Structural Changes) Order 2019", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 2019/957, retrieved 30 March 2024

- ^ "Local Government Act 1972: Section 245", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1978 c. 70 (s. 245)

- ^ "Change of name from Parish to Town Council". Gerrards Cross Parish Council. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2025.

- ^ "Tesco restarts work at tunnel collapse site". New Civil Engineer. 14 January 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ "The hunt for Britain's Ghost Trains". The Independent. 19 December 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ "Census Maps - Census 2021 data interactive, ONS".

- ^ "Census Maps - Census 2021 data interactive, ONS".

- ^ [1969] 1 AC 454

- ^ "Dominic Raab – the Bucks-born MP who is now Britain's de facto Prime Minister".

- ^ Now MagazineApr 21; Edt, 2017 11:18 Am. "Now meets Peter Stringfellow: 'I'm so loved up with my wife Bella!'". celebsnow.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Duncan, Amy (7 June 2018). "Peter Stringfellow net worth, wife and children after death from cancer battle". Retrieved 6 April 2020.

External links

[edit]- Gerrards Cross Community Association GXCA https://www.gxca.org.uk/

- Gerrards Cross Library